Ekaterina Arapova PhD in Economics, Head of Department of Assessment and Coordination of International and Duel Master’s Degree Programs, MGIMO-University, MFA of Russia

Turmoil

On August 11–13, 2015, the People’s Bank of China devalued the national currency by 3.5 per cent in a logical move that nevertheless came as an unexpected and unpleasant surprise to market participants [1]. The devaluation can be seen as a signal that China is changing its strategy for the country’s economic growth and its position on the global markets and within the world financial system.

A Return to an Export-Oriented Economy?

After the unprecedented slump on the Chinese stock market in late July 2015, when the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index tumbled by 8.5 per cent [2] (which was a natural consequence of the accumulated structural imbalances of the Chinese economy and the slowdown in global trade), it became clear that the government and the fiscal authorities would waste no time in resorting to measures to stimulate the national economy and relieve panic on the financial markets, reduce speculative pressure and maintain economic growth rates.

For a long time, China’s economic strategy was to a great degree focused on expanding trade, stimulating exports and accumulating international reserves thanks to high export revenues.

The devaluation of the yuan raises two important questions:

Firstly, will the exchange rate formation mechanism once again become one of the main tools for maintaining high rates of economic growth, and can we expect a return to the undervalued yuan and a new wave of “currency wars”?

Secondly, how will the measures currently being taken affect China’s position on the global markets, the decisions of its key partners and the implementation of its strategic foreign economic policy?

The devaluation of the yuan can be seen as an historical step that proves China’s willingness to take active measures to regulate crises should they arise, despite its declared intention to move to market management mechanisms. It also indirectly confirms that the strategy to diversify the growth of the country’s economy will not be easy in the short term, and perhaps the medium term as well.

The authorities have been thinking about the need for structural reform for a long time. A new course was set with the aim of strengthening domestic demand, reducing the dependence on foreign markets and transitioning to a “market economy” in the development of the economy and the exchange rate formation mechanism.

For a long time, China’s economic strategy was to a great degree focused on expanding trade, stimulating exports and accumulating international reserves thanks to high export revenues. From 1998 to 2007, exports of goods and services grew by an average of 18.5 per cent annually [3]. The average size of current accounts was 4 per cent of the country’s GDP [4], while foreign currency reserves grew by an average of 27.5 per cent per year over the same period. The high price competitiveness of Chinese products was achieved by the low cost price of the goods themselves, as well as by the introduction of additional mechanisms to stimulate export – including artificially lowering the value of the yuan.

When, in 2005, Congressmen Charles Schumer and Lindsey Graham introduced a bill on setting duties on goods brought in from China at 27.5 per cent, the yuan was undervalued by as much as 40 per cent, according to experts [5]. From 2005 to 2013, the yuan rose by 34 per cent in nominal terms, and 42 per cent in real terms [6].

The decrease in the net surplus of current operations, coupled with the slowdown in the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves, have led to a significant reduction in the gap between the nominal and real cost of the Chinese currency, reducing the significance of the yuan exchange rate as a major factor ensuring the competitiveness of Chinese products on foreign markets and, consequently, the intensity of the co-called currency wars.

China is striving to develop a dialogue with all countries, not just those in East Asia or even the Asia-Pacific Region.

The transition to a market exchange rate formation mechanism, along with the reforms aimed at stimulating domestic demand and investments [7], were designed to promote the re-orientation of the Chinese economy, lower the dependency on exports and help adapt to current trends in global economic development after the crisis of 2008—2009.

However, we are still to see significant results in transforming domestic demand into a driver for economic growth in China. There is increased deflationary pressure on the economy (inflation fell from 10.4 per cent in 2010 to 2.6 per cent in 2013 and 2 per cent in 2014 [8]. The level of gross national savings remains relatively high (51.4 per cent of GDP); however, the contribution of the private sector to GDP growth in recent years has accounted for only slightly more than one third, while the average figure for developing countries in the Asia-Pacific Region is 55 per cent [9].

While domestic demand is not able to compensate symmetrically for the stuttering the Chinese economy as a result of the slowdown in foreign trade, the Chinese authorities are, in addition to adopting a packet of measures to stimulate demand in this area, trying to stabilize foreign trade flows and return to traditional growth strategies. The devaluation of the yuan is aimed primarily at expanding trade.

On All Fronts

The devaluation of the yuan is aimed primarily at expanding trade.

Despite the economic slowdown — in March 2015, the Chinese government adjusted its GDP growth target for 2015 to 7 per cent from the previous figure of 7.5 per cent [10] — China has been moving confidently towards expanding its economic presence around the world in various sectors. At the same time, an obviously balanced approach can be seen in the geographical structure of China’s foreign economic relations: China is striving to develop a dialogue with all countries, not just those in East Asia or even the Asia-Pacific Region. Bilateral regional trade agreements have been signed with a number of Asian partners (India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, the ASEAN countries and South Korea), as well as with New Zealand, Switzerland, the Republic of Ireland, Costa Rica, Peru and Chile. China also has a number of bilateral foreign currency swap agreements with various regions around the world [11].

Part of the policy of “economic expansion” is determined by China’s desire to realize its ambitious plans to raise the country’s profile, not only in the global trade system, but also in the financial sector — partly through objective factors: the slowdown in world trade [12] and deflationary pressure on the country’s economy [13], outstripping population growth in comparison with food production, forcing the country to look for new ways to replenish food stocks, as well as the desire to strengthen global and regional stability.

Until recently, China sought to diversify its sources of economic growth, gradually move away from its export-oriented development strategy and pursue a balanced policy of expanding its economic presence, not only in the structure of global trade flows, but also in a number of other areas, thus demonstrating different aspects of its “economic expansion”:

“foreign currency expansion” — by actively implementing the strategy to internationalize the yuan [14], which was adopted in 2009, and developing a network of bilateral swap agreements between the People’s Bank of China and the central banks of partner countries;

“territorial expansion” — by actively investing in the implementation of large-scale, long-term infrastructure projects and purchasing land plots to be used in accordance with China’s strategic priorities;

“labour expansion” — by exporting labour as a relatively abundant production factor. Excess production capacity, supply outstripping demand and the resulting increased deflationary pressure on the economy lead to more and more people leaving the country to find employment [15].

China is striving to develop a dialogue with all countries, not just those in East Asia or even the Asia-Pacific Region.

With Chinese companies investing abroad on a greater scale, and labour-intensive investment projects being actively implemented, islands of “Chinese civilization” are slowly growing in number.

However, the recent troubles on the stock market and the subsequent devaluation of the national currency could lead to significant changes in China’s strategic foreign economic priorities, reinvigorating certain areas of “economic expansion” while putting others on the back burner.

Internationalizing the yuan

Despite the unprecedented devaluation, it is still too early to talk about a return to the policy of having an undervalued yuan.

One of China’s foreign economic priorities in recent years has been to increase the significance of the yuan in the global financial system.

The process of internationalizing the yuan got a shot in the arm in 2009 with the launch of the Pilot Program of RMB Settlement of Cross-Border Trade Transactions [16]. By 2013, the yuan was the eighth most traded currency in the world [17].

This was achieved primarily thanks to China developing a network of bilateral swap agreements with its key trading partners around the world. In the run-up to, and throughout the first few years of, the programme to internationalize the yuan, China mostly signed agreements with its traditional East Asian partners — South Korea (December 2008), Hong Kong (January 2009), Malaysia (February 2009), Indonesia (March 2009) and Singapore (July 2010). It then began to carry out a more geographically balanced foreign economy policy with regard to internationalizing the yuan, signing agreements with Brazil (March 2013), the United Kingdom (June 2013), the European Union (October 2013), Switzerland (July 2014), Qatar (November 2014), Canada (November 2014), South Africa (April 2015) and others [18].

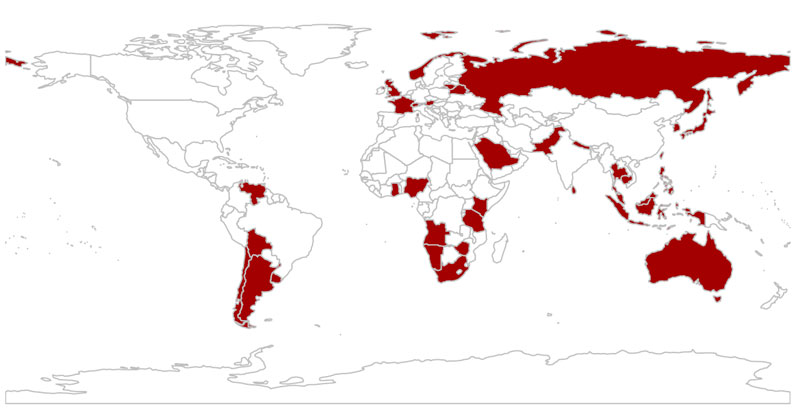

The success of the Chinese government’s strategy to internationalize its currency has resulted in the central banks of 37 countries holding assets in yuan [19] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of Countries Holding Chinese Yuan as Part of their Reserves

Source: Steven Liao, Daniel E. McDowell. No Reservations: International Order and Demand for the Renminbi as a Reserve Currency. Draft: March 26, 2015, p. 4.

Source: Steven Liao, Daniel E. McDowell. No Reservations: International Order and Demand for the Renminbi as a Reserve Currency. Draft: March 26, 2015, p. 4. Available at:

The yuan is still not recognized by the IMF as a “legal reserve currency”, although negotiations on the matter are ongoing [20].

The devaluation of the yuan and the increased risks associated with it would appear to damage the prospects for turning the renminbi into a global reserve currency. But it is precisely these factors that could help to further develop the network of bilateral swap agreements.

The devaluation of the yuan and the increased risks associated with it would appear to damage the prospects for turning the renminbi into a global reserve currency. But it is precisely these factors that could help to further develop the network of bilateral swap agreements. One of the main aims for entering into such agreements is to reduce the risks associated with currency fluctuations. Currency swap agreements can benefit all sides: China, as they help stabilize trade flows and the yuan reserves of other countries; and China’s key trading partners, because under the circumstances it is clear that China will try to resist the strengthening of its currency, meaning that payments (and calculating the costs of transactions) in yuan will end up being profitable for importers.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Interests

Despite the unprecedented devaluation, it is still too early to talk about a return to the policy of having an undervalued yuan. Representatives from the People’s Bank of China have talked about the prospects of the yuan’s appreciation in the near future. The significant currency reserves, along with the trade surplus and stable fiscal position, are designed to ensure that the national currency gets stronger. Rather, we are talking about temporarily redressing the balance at a time when exports have dropped sharply under internal and external pressure and government policies aimed at increasing household consumption have failed to yield the expected results.

In the short term, we can expect a slight increase in foreign trade as a result of improving the price competitiveness of Chinese products – primarily with its regional partners (in the ASEAN+China format), where there is a relatively high level of price elasticity. The investment activity of Chinese companies on foreign markets could slow down somewhat in the short term, although the “object approach” in relations with potential partner countries will remain, and technology exports will also involve the export of labour.

The Asian–African vector of China’s investment policy is evident. The majority of China’s investment projects to develop agricultural areas are being carried out in Africa and partner countries in East Asia with the emphasis gradually shifting towards relatively less developed countries, which can become dependent on Chinese investments in a number of areas. Potential partners are often characterized by an abundance of natural resources, a favourable geographic position and a relatively low availability of human resources (by size and population density), or the inability to fully exploit existing assets.

The Asian–African vector of China’s investment policy is evident.

The imbalance of economic growth sources that has formed could push China to become more actively involved in integration processes in the Asia-Pacific Region and carrying out the project to set up an Asian-Pacific free trade zone. The devaluation of the yuan may help expand the network of bilateral currency swap agreements.

In the long term, China will continue to focus on carrying out its strategies to diversify sources of economic growth, reduce its dependence on exports and expand its economic presence on the global capital markets and in the world financial system.

Sources:

1. China lets yuan fall further, fuels fears of ‘currency war’ // Reuters. August 12, 2015. Available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/08/12/us-china-markets-yuan-idUSKCN0QG04U20150812

2. Chinese Stock Market Suffers Collapse, Hits Eight-Year Low // ВВС Russia. July 27, 2015. http://www.bbc.com/russian/business/2015/07/150727_china_shares_fall (in Russian)

3. World Economic Outlook Statistic Database. IMF. April 2015.

4. Ibidem.

5. Athavaley A. Schumer, Graham May Press for China Tariffs. Washington Post Staff Writer. Friday, July 29, 2005. Available at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/28/AR2005072802040.html

6. Morrison W. Labonte M. China’s Currency Policy: An Analysis of the Economic Issues. Congressional Research Service. CRS Report for Congress. Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress. July 22, 2013.

7. Third Plenum Economic Reform Proposals: A Scorecard / U.S.–China Economic and Security Review Commission. Staff Research Backgrounder. November 19, 2013. Available at: http://origin.www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Backgrounder_Third%20Plenum%20Economic%20Reform%20Proposals–A%20Scorecard%20(2).pdf

8. Making Growth More Inclusive for Sustainable Development. Economic and Social Survey of Asia and the Pacific 2015 / UNESCAP.

9. The People’s Bank of China, News. PBC. Accessed April 2015.

10. Regional Connectivity for Shared Prosperity. Economic and Social Survey of Asia and the Pacific. UN. Bangkok, 2014, p. 39.

11. Highlights of China’s gov’t work report for 2015. Available at: http://www.china.org.cn/china/NPC_CPPCC_2015/2015-03/05/content_34957640.htm

12. Trade and Development Report, 2013, 2014. UNCTAD. New York, Geneva, 2013, 2014.

13. See Arapova, E. China’s “Great Depression Syndrome”? Russian International Affairs Council. http://russiancouncil.ru/inner/?id_4=5631#top (in Russian).

14. Renminbi Trade Settlement Pilot Scheme // Hong Kong Monetary Authority Quarterly Bulletin. September 2009.

15. See, for example, Arapova, E. China’s “Great Depression Syndrome”? Russian International Affairs Council. http://russiancouncil.ru/inner/?id_4=5631#top (in Russian).

16. Garcia-Herrero A., Le Xia China’s RMB bilateral swap agreements: What explains the choice of countries? / Bank of Finland, BOFIT Institute for Economies in Transition. BOFIT Discussion Papers. No. 12, 2013, p. 6.

17. Bank for International Settlements Report. September 2013.

18. The People’s Bank of China, News. PBC. Accessed April 2015.

19. Liao S., McDowell D. No Reservations: International Order and Demand for the Renminbi as a Reserve Currency. Draft: March 26, 2015, p. 4.

20. China-IMF talks underway to endorse yuan as global reserve currency // The BRICS Post. March 12, 2015. Available at: http://thebricspost.com/china-imf-talks-underway-to-endorse-yuan-as-global-reserve-currency/#.VUEtKabWiUk

Source: http://russiancouncil.ru/en/inner/?id_4=6499#top-content

October 15, 2015

October 15, 2015

Опубликовано в

Опубликовано в